A STORY ABOUT ...

alluvial soil nurturing the grapes

for renowned California Wines

volcanic soil carrying the aromas

of Celebrated colombian coffee

clay-limestone soil norishing the trees

of acclaimed italian olives

... THE SOILS

Story of the Soils

Farmlands are the cultivating grounds of resources necessary to sustain life and society, shaped not only by the hands of farmers but by the deeper foundation beneath them: the soils.

When considering the outputs of agricultural activities, the Socio-Economic Challenges faced by the farmers - such as the lack of afforable and appropriate housing - are indeed a factor of influences. Soils, on the other hand, is another direction of intervention, as they set the baseline for what can ultimately thrive - determining crops, yields, and even the taste of harvests. They store and filter water, recycle nutrients, and sustain the unseen ecosystems that make agriculture possible.

In fact, 95% of the world's food is grown in the thin layer of nutritious topsoils, a resource that takes centuries to form but only decades to deteriote. It is thus noteworthy of the immense value of prime soils and the urgent importance to preserve them.

Grow Edible Homes

Approaching more sustainable agricultural practices, with the aspiration of additional architectural applications to then replenish the labor and resources needed in farming, perhaps hints a solution to the aforementioned challenges...

To examine the possibility and affordability of "growing" materials and houses, the rural and urban farming conditions are to be measured and evaluated, specifically looking at the available farmable soils and the potential opportunities/obstacles to utilize them. In face of remaining difficulties, alternative agricultural practices are investigated, in hope to find an adaptive farming strategy to achieve architectural renewability.

What is "Farmable"

To be classified as a "farmland" under USDA standards requires the best physical and chemical characteristics for growing crops, including adequate and dependable supply of moisture, favorable temperature and growing season, acceptable acidity or alkalinity, acceptable salt and sodium content, permeable to water and air, not excessively erodible or saturated, not frequently flooded, slope ranges mainly from 0 to 6 percent, and few or no rocks.

Pittsfield Gravelly Loam

The Pittsfield gravelly loam of Orange County, New York, was formed during the Wisconsinan Glaciation (17,000-15,000 years ago), when the Hudson Lobe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet scoured bedrock and deposited a stony, calcareous glacial till rich in limestone and schist fragments. After ice retreat, this parent material weathered under a mesic climate, accumulating organic matter and developing distinct horizons. Found on uplands, drumlinoid ridges, and slopes, Pittsfield soils are typically deep, well drained, and moderately fertile, with their gravelly texture reflecting their glacial origins.

It is classified as "prime farmland" mainly for its deep, well-drained profile, moderate fertility, and favorable texture provide reliable rooting depth, good aeration, and sufficient water-holding capacity for crops.

Alden Silt Loam

The Alden silt loam of Orange County, New York, was formed in depressions on glacial till plains where fine silts accumulated after the last ice age. Its parent materials include glacial till of mixed rock fragments overlain by a silty mantle, which settled in low-lying areas. Prolonged saturation led to the development of a Mollic Endoaquept, marked by a dark, organic-rich surface horizon, weakly developed subsoil, and poor drainage throughout the profile. Classified as a hydric soil, Alden supports wetland vegetation and remains saturated much of the year, limiting its agricultural use despite high surface fertility.

It is classified as "not prime farmland" because its poor natural drainage and persistent high water table create saturated conditions that severely restrict crop growth and field use.

-0

-10

-34

-60

0-

9-

36-

60-

Silt Loam Topsoil

Fertile, but poorly drained and slightly acidic

Silt Loam Subsoil

Seasonally saturated, restricted rooting, nutrient leaching

Gravelly Fine Sandy Loam Substratum

Poor top drainage

Gravelly Loam Topsoil

Fertile, well drained, granular

Gravelly Loam Subsoil

Firm yet permeable, unrestricted rooting, improved aeration

Gravelly Sandy Loam Substratum

Permeable

Depth (in)

Farmable Soils

the amount of farmable soils available in Orange County (Rural) and New York City (Urban) Based on USDA Farmland Classification are investigated to reveal the distribution and the potential For Farmlands in the differing regions.

3.0%

1.4%

0.1%

1.5%

97.0%

New York City

48.0%

5.8%

1.6%

40.6%

52.0%

Prime farmland is land that has the best combination of physical and chemical characteristics for producing food, feed, forage, fiber, and oilseed crops. It is available for these uses (i.e., not water, urban, or built-up land) and can economically produce sustained high yields of crops when treated and managed according to acceptable farming methods, including water management.

Prime farmland if drained refers to soils that meet all the criteria for prime farmland, except that they are too wet in their natural state. These soils can qualify as prime farmland only if artificial drainage is installed and maintained (for example, through tile drains, ditches, or other systems).

Farmland of Statewide Importance is land, in addition to prime farmland, that is important for the production of food, feed, fiber, forage, and oilseed crops as determined by each state’s agencies. It generally represents a second tier of agricultural land quality - having minor limitations such as slope, drainage, shorter growing seasons, or lower water capacity.

Not prime farmland refers to land that does not meet the criteria for prime farmland, farmland of statewide importance, or farmland of local importance. These areas generally have severe limitations that make them unsuitable for sustained agricultural production, even with significant management or improvements.

Orange County

Not Prime Farmland

?

Farmland of State Importance

?

Prime Farmland if Drained

?

Prime Farmland

?

Overlaps

Evaluating the farmable soils' overlaps with agricultural districts/urban farms, Building footprints, and forests suggests differing farmland use obstacles and opportunities, as well as implications for alternative strategies in rural and urban settings.

Farmable Land

Unfarmable Land

Inside of Farmable Lands

47.4%

Outside of Farmable Lands

52.6%

Outside of Farmable Lands

39.2%

Inside of Farmable Lands

60.8%

Orange County

Add paragraph text. Click “Edit Text” to update the font, size and more. To change and reuse text themes, go to Site Styles.

Agricultural Districts

Add paragraph text. Click “Edit Text” to update the font, size and more. To change and reuse text themes, go to Site Styles.

Forests

Add paragraph text. Click “Edit Text” to update the font, size and more. To change and reuse text themes, go to Site Styles.

Forests

Building Footprints

Agricultural Districts

Farmable Land

Farmable Land Occupation

35.7%

Inside of Farmable Lands

60.8%

Outside of Farmable Lands

39.2%

Farmable Land Occupation

2.2%

Inside of Farmable Lands

72.1%

Outside of Farmable Lands

27.9%

Farmable Land Occupation

1.9%

Inside of Farmable Lands

47.4%

Outside of Farmable Lands

52.6%

Orange County

With nearly half (48%) of the land classified as suitable for agricultural practices, Orange County chosen as an examplar of rural regions reflects the large availability of farmable soils and great potential for field farming.

Agricultural Districts

35.7% of the farmable lands are utilized as agriculture districts; a considerable amount of good soils is yet to be cultivated.

Within the agricultural districts, 60.8% of the lands are suitably farmable, leaving 39.2% of the farms situating in poor soils with reduced productivity and elevated costs. Considering the available topsoils elsewhere, it can be advised that some districts be translated to empty plots.

Farmland Overlaps

Building Footprints

Only 2.2% of the farmable lands are occupied by buildings; thanks to the rather scattered inhabitation of the relatively small population, as well as the negligible footprint of rural structures, buildings are generally not a physical constraint to farming practices.

Despite the insignificant footprint of buildings in Orange County, 72.1% of the structures are still sited on farmable soils; considering the additional impacts of constructions (excavation, runoffs, infrastructure), more lands might be contaminated. Future planning thus needs to be more thoughtful of the soil conditions.

Farmland Overlaps

Forests

Only 1.9% of the farmable lands are occupied by forests; if more lands are needed for agricultural practices, little deforestation is required.

Despite the insignificant footprint of forests in Orange County, to free up the good soils for farming still requires the removal of half the amount of trees, hence should not be considered as a productive strategy.

Farmland Overlaps

Forests

Building Footprints

Agricultural Districts

Farmable Land

Farmable Land Occupation

0.01%

Inside of Farmable Lands

0.6% (3)

Outside of Farmable Lands

99.4% (618)

Farmable Land Occupation

0.6%

Inside of Farmable Lands

0.1% (822)

Outside of Farmable Lands

99.9% (1,087,612)

Farmable Land Occupation

48.1%

Inside of Farmable Lands

21.8%

Outside of Farmable Lands

78.2%

New York City

With barely any (3.6%) land classified as suitable for agricultural practices, New York City chosen as an examplar of urban regions reflects the little availability of farmable soils and encourages alternative strategies to sustain agricultural production, if necessary.

Urban Farms

Of the already insignificant amount of farmable soils, only 0.01% are utilized directly for farming. More lands can indeed be considered for agriculture, but the density of the city and the cost of land all seem to impose challenges to such practices.

Considering that 99.4% of urban farms occur outside of farmable lands, an urbanistic strategy of agriculture can be seen, in which artificially constructed plots and pots support the occasional cultivation of crops.

Farmland Overlaps

Building Footprints

Farmland Overlaps

Of the already insignificant amount of farmable soils, only 0.6% of the lands are occupied by buildings. Considering the density of the buildings, however, it can be deduced that potentially good soils might have been removed upon construction, leaving only the untouched areas in their prestine conditions.

Considering that only 0.1% of the buildings are inside of farmable lands, the statement that urban constructions heavily deteriorate the soil might thus be reinforced. With the significant impacts in mind, future planning should be considerate of preserving the remaining bits of prime soils.

Forests

Farmland Overlaps

Unlike the other overlaps, forests actually cover 48.1% of the farmable lands; it is noted that prime soils in urban regions might have been cultivated or preserved for the growth of natural vegetation.

While only 21.8% of the trees are fertilized by prime soils, they mostly situate near the center of the regional forests; it can be deduced that the outer rings of the forests face more frequent disturbance and contamination, and thus the removel of trees for agriculture doesn't seem necessary or adequate, as faster deterioration is to be expected.

Forests

Building Footprints

Urban Farms

Forests

Building Footprints

Agricultural Districts

Farmable Land

Unfarmable Land

New York City

Add paragraph text. Click “Edit Text” to update the font, size and more. To change and reuse text themes, go to Site Styles.

Construction Development Impacts

Excavation, Pollutions, Runoffs

Implications:

Building development and land resources exist in a complex, reciprocal relationship: on one hand, urban expansion often consumes farmland directly, sealing fertile soil beneath concrete and fragmenting agricultural landscapes, while construction processes can further degrade surrounding ecosystems through erosion, runoff, and pollution. Yet paradoxically, the very act of development also produces one of the main reservoirs of reusable soil. Excavated earth from building foundations, roadworks, and infrastructure projects frequently becomes the raw material for land reclamation, soil remediation, and even urban farming.

Building Development

1. Physical Disturbance and Soil Structure

-

Excavation, grading, and compaction during construction fundamentally alter soil structure. Heavy machinery compresses soil layers, reducing porosity, infiltration, and root penetration.

-

Soil sealing by impervious surfaces (roads, roofs, pavements) prevents gas exchange, increases bulk density, and disrupts microbial habitats.

-

Studies show that soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) in the top 10 cm are reduced by over 60% beneath homes compared to lawns, with microbial biomass also significantly lower.

2. Soil Erosion and Sediment Yield

-

Exposed soil on construction sites erodes at rates up to 2–40,000 times higher than natural conditions, mobilizing sediment into streams.

-

Paired watershed studies in South Carolina found sediment yields during active development were 60–90× higher than in reference basins.

-

Urbanization globally accelerates soil erosion by 7–72×, depending on rainfall intensity: drier regions show ~12× increase, wetter areas up to ~70×.

3. Loss of Fertility and Topsoil

-

Topsoil, which takes centuries to form, is often stripped or mixed with subsoil during construction, leading to permanent loss of organic matter and nutrients.

-

In China, post-construction soils showed organic matter decreases of 250–880% compared to pre-construction levels.

-

Websites confirm that raindrop impact on bare soils and altered drainage dramatically increase runoff, further degrading soil fertility and leading to downstream flooding.

4. Hydrological Impacts

-

Soil compaction and sealing reduce infiltration, raising stormwater volumes and peak flows. Developed watersheds experience 2–9× higher runoff than undeveloped ones.

-

This intensifies urban flooding and contributes to stream channel erosion, sedimentation, and long-term geomorphic instability.

5. Broader Ecological and Social Effects

-

Aquatic ecosystems suffer from high sediment loads, which smother fish eggs, clog gills, and reduce light penetration.

-

Soil degradation undermines urban agriculture potential, biodiversity, and ecosystem services (e.g., carbon storage, stormwater buffering, cooling).

-

The economic cost of sediment-related water degradation and restoration reaches billions annually in the U.S.

-

Excavation, grading, and compaction during construction fundamentally alter soil structure. Heavy machinery compresses soil layers, reducing porosity, infiltration, and root penetration.

-

Soil sealing by impervious surfaces (roads, roofs, pavements) prevents gas exchange, increases bulk density, and disrupts microbial habitats.

-

Studies show that soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) in the top 10 cm are reduced by over 60% beneath homes compared to lawns, with microbial biomass also significantly lower.

-

-

Exposed soil on construction sites erodes at rates up to 2–40,000 times higher than natural conditions, mobilizing sediment into streams.

-

Paired watershed studies in South Carolina found sediment yields during active development were 60–90× higher than in reference basins.

-

Urbanization globally accelerates soil erosion by 7–72×, depending on rainfall intensity: drier regions show ~12× increase, wetter areas up to ~70×.

-

-

Topsoil, which takes centuries to form, is often stripped or mixed with subsoil during construction, leading to permanent loss of organic matter and nutrients.

-

In China, post-construction soils showed organic matter decreases of 250–880% compared to pre-construction levels.

-

Websites confirm that raindrop impact on bare soils and altered drainage dramatically increase runoff, further degrading soil fertility and leading to downstream flooding.

-

-

Soil compaction and sealing reduce infiltration, raising stormwater volumes and peak flows. Developed watersheds experience 2–9× higher runoff than undeveloped ones.

-

This intensifies urban flooding and contributes to stream channel erosion, sedimentation, and long-term geomorphic instability.

-

-

Aquatic ecosystems suffer from high sediment loads, which smother fish eggs, clog gills, and reduce light penetration.

-

Soil degradation undermines urban agriculture potential, biodiversity, and ecosystem services (e.g., carbon storage, stormwater buffering, cooling).

-

The economic cost of sediment-related water degradation and restoration reaches billions annually in the U.S.

-

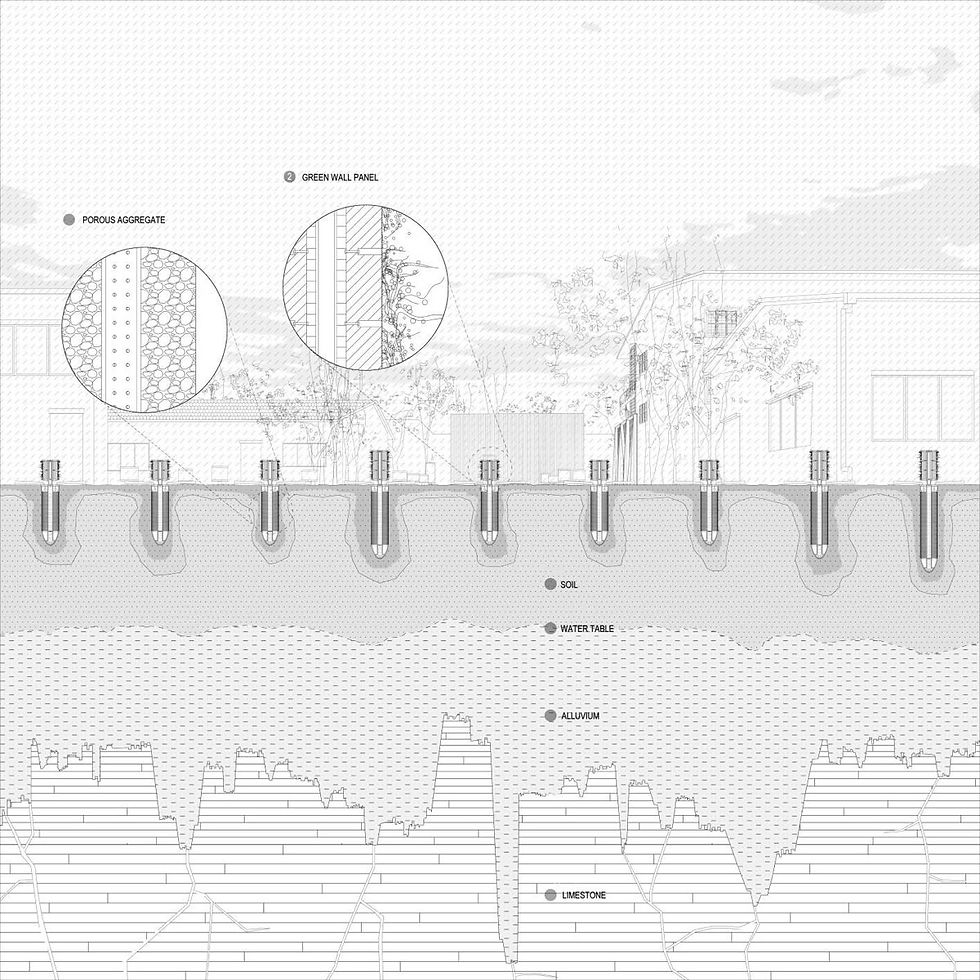

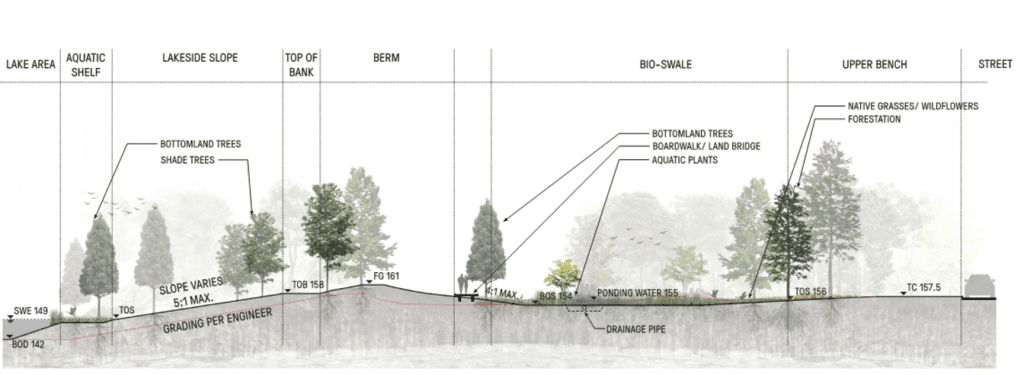

Low Impact Development

As building development often leaves soils stripped, compacted, and degraded. Heavy machinery and grading remove topsoil and organic matter, while impervious surfaces seal off infiltration, accelerating runoff and erosion. What was once a porous, living system becomes functionally dead ground—unable to absorb water, filter pollutants, or sustain healthy vegetation.

Low Impact Development (LID) emerged as a direct response to this problem. At its core, LID is about protecting and restoring soils so they can continue performing their natural roles: absorbing rainfall, filtering contaminants, recharging groundwater, and supporting plant life. In this sense, LID is not just stormwater management—it is fundamentally soil management, ensuring that development works with the soil rather than against it.

-

Healthy soils are living systems with microbial and root networks that cycle nutrients, improve structure, and support vegetation.

-

LID fosters these systems by reducing chemical inputs and maintaining organic matter, reducing long-term reliance on fertilizers or pesticides.

Techniques:

-

Organic soil amendments in planting beds

-

Urban tree plantings with adequate rooting volume

-

Rainwater harvesting (cisterns/barrels) to prevent soil over-saturation and nutrient leaching

Sustaining Soil Biology and Fertility

-

Soil is a natural filter for sediments, nutrients, and contaminants. LID practices route runoff through vegetated and amended soils that trap and break down pollutants before they can degrade larger soil or water systems.

Techniques:

-

Bioswales and vegetated filter strips

-

Tree box filters (soil-root systems)

-

Constructed wetlands with soil-plant-microbial treatment zones

Filtering Pollutants Through Soil Systems

-

By allowing water to soak into soils instead of running off hard surfaces, LID reduces erosion and replenishes groundwater.

-

The design distributes infiltration across the landscape rather than concentrating it at a single point.

Techniques:

-

Bioretention cells and rain gardens (engineered soil media)

-

Infiltration trenches and dry wells

-

Permeable pavements that protect subsoils while allowing infiltration

Enhancing Infiltration and Groundwater Recharge

-

Where soils are already disturbed, LID prescribes soil restoration standards: adequate uncompacted depth, organic matter content, and pH balance.

-

Restored soils regain infiltration capacity, moisture retention, and vegetation support.

Techniques:

-

Subsoil scarification/loosening

-

Compost amendment or imported topsoil

-

Reapplication of stripped and stockpiled topsoil

-

Setting soil depth standards (e.g., 30 cm for turf/planting, 90 cm for tree pits)

Restoring Soil Function After Construction

-

Development often leaves soils stripped, compacted, and bare, destroying their infiltration capacity.

-

LID emphasizes site stabilization during construction: phasing earthworks, covering bare soils with mulch or blankets, and preserving natural buffers.

-

These measures protect soil structure, microbial communities, and topsoil fertility.

Techniques:

-

Erosion-control blankets and mulching

-

Buffer zones around undisturbed soils

-

Phased grading and runoff diversion

Preventing Compaction and Erosion

Soil Surplus

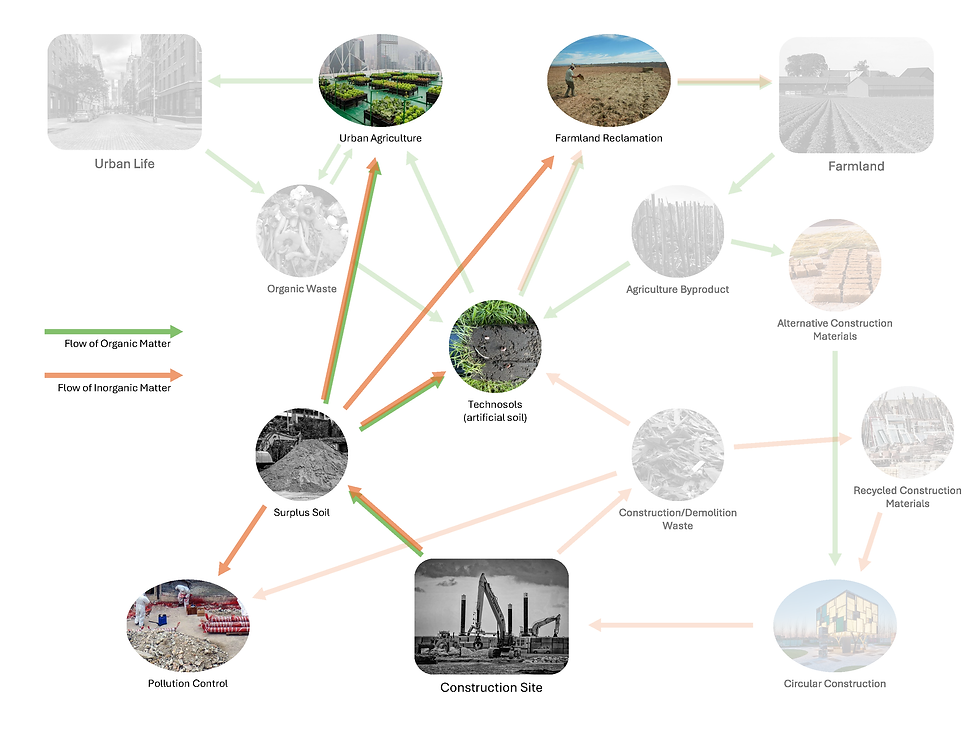

Urban life, agriculture, and construction Should not Be separate systems but parts of the same material cycle. Every byproduct—organic waste, surplus soil, demolition debris—carries the potential to become input for another process.

In New York City alone, construction activities produce ~ 1.7 million tons of surplus clean native soil (mainly glacial sediments)

Service Name

Subtitle Goes Here

This is the space to introduce the Services section. Briefly describe the types of services offered and highlight any special benefits or features. Encourage site visitors to learn more by exploring the full list of services offered.

Write a Title Here

Subtitle Goes Here

Share information on a previous project here to attract new clients. Provide a brief summary to help visitors understand the context and background of the work.

Write a Title Here

Subtitle Goes Here

Share information on a previous project here to attract new clients. Provide a brief summary to help visitors understand the context and background of the work.

Renewable Crops

Suitable for Orange County (Rural) and New York City (Urban)

Crops Catalog

Document suitable crops to be grown in rural and urban settings based on soil requirement

New York City

Orange County

Soil

Add paragraph text. Click “Edit Text” to update the font, size and more. To change and reuse text themes, go to Site Styles.

I1S5

I1S4

I1S3

I1S2

I1S1

Item 1

Description for Item 1

Research + Design Advanced Studio