Research + Design Advanced Studio

Farms Feed Cities.

But who sustains the farms?

And how do we sustain them?

Source: John Moore/Getty Images

Nearly three million farmworkers sustain U.S. food production. Yet, their wages have risen far more slowly than food prices, leaving many unable to afford the very food they help grow.

Source: Farmworker Wages, Food Prices

The people behind our food

During COVID, farmworkers were classified as essential workers, the ones who kept fields picked and food moving. Yet essential sectors, including food and agriculture, suffered some of the highest COVID risks and excess mortality. That contrast still frames this story: the work is essential, the people are vulnerable.

Most hired crop workers are immigrants. In recent NAWS data, about four in ten lacked work authorization. At the same time, growers increasingly rely on the H-2A program, which certified roughly 379,000 positions in FY2023.

Nearly three million farmworkers sustain U.S. food production. Yet, their wages have risen far more slowly than food prices, leaving many unable to afford the very food they help grow.

The people behind our food

Who grows our food? Farmworkers are young and old, men and women, migrants and residents. Knowing who they are is the first step to understanding the challenges they face.

Who is a Farm Worker?

The workforce is aging and more settled, with an average age near 39 and only a small share now following multi-state harvests. Many workers have limited formal schooling, on average around the ninth grade, which narrows options beyond farm work.

Women make up about a quarter of hired farmworkers, a share that has risen. One reason is the adoption of labor-saving tools such as hydraulic platforms and mobile conveyors, which reduce heavy lifting and make more tasks accessible to women and older workers.

Patterns of Settlement

Farmworkers live in rhythms of movement and settlement. Some arrive for a single season, others return year after year, and many put down roots permanently. These shifting patterns determine whether housing is temporary, shared, or a place that can sustain family life.

Patterns of settlement

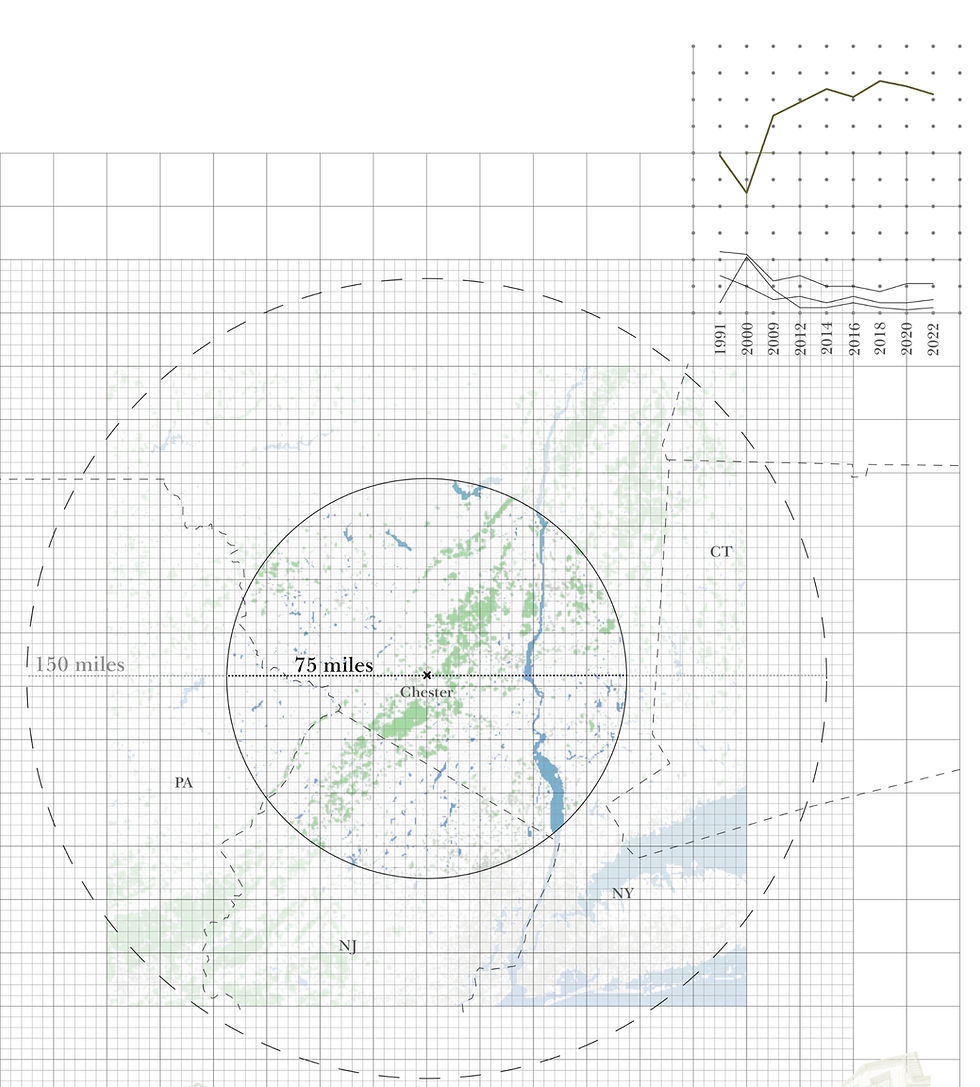

Most crop farmworkers today are settled rather than migrant. In recent surveys, roughly four in five workers are classified as settled. Under NAWS, “settled” simply means a worker’s job is within 75 miles of home, which is still a long distance to cover for daily life and family routines. “Migrant” means a move of at least 75 miles to get farm work or to switch jobs, a line that sorts the workforce but hides how far a “settled” commute can stretch daily life.

How far is “settled”? A 75-mile (≈121 km) radius from Chester, N.Y., shows the extent, which includes Manhattan.

Source: Global Croplands Data

Seasonality then shapes the home. Settled year-round workers may rent or own nearby, while settled seasonal crews often double up or shuffle short sublets at harvest. Migrant seasonal crews depend on employer or temporary housing, and migrant year-round placements, including many on H-2A, live where the job dictates.

This map centers on Chester, New York, an agricultural hub in the Hudson Valley. The Chester Agricultural Center brings together multiple farms, employing both local workers and migrant laborers who travel from across the region. Its location makes it a useful lens for seeing how settlement and mobility play out in real farmworker lives.

Settled Farmworker

Settled crop workers are employed at locations that are within 75 miles of each other.

Seasonal Farmworker

Works only during planting or harvest periods; employment is temporary and tied to crop cycles

Add a text about how majority of workers are settled!

As more jobs run year-round and more workers put down roots, pressure grows on already scarce rural housing. Understanding who is moving and who is staying, and when the work begins and ends, clarifies why living conditions vary so widely and where design, planning, and policy can close the gap.

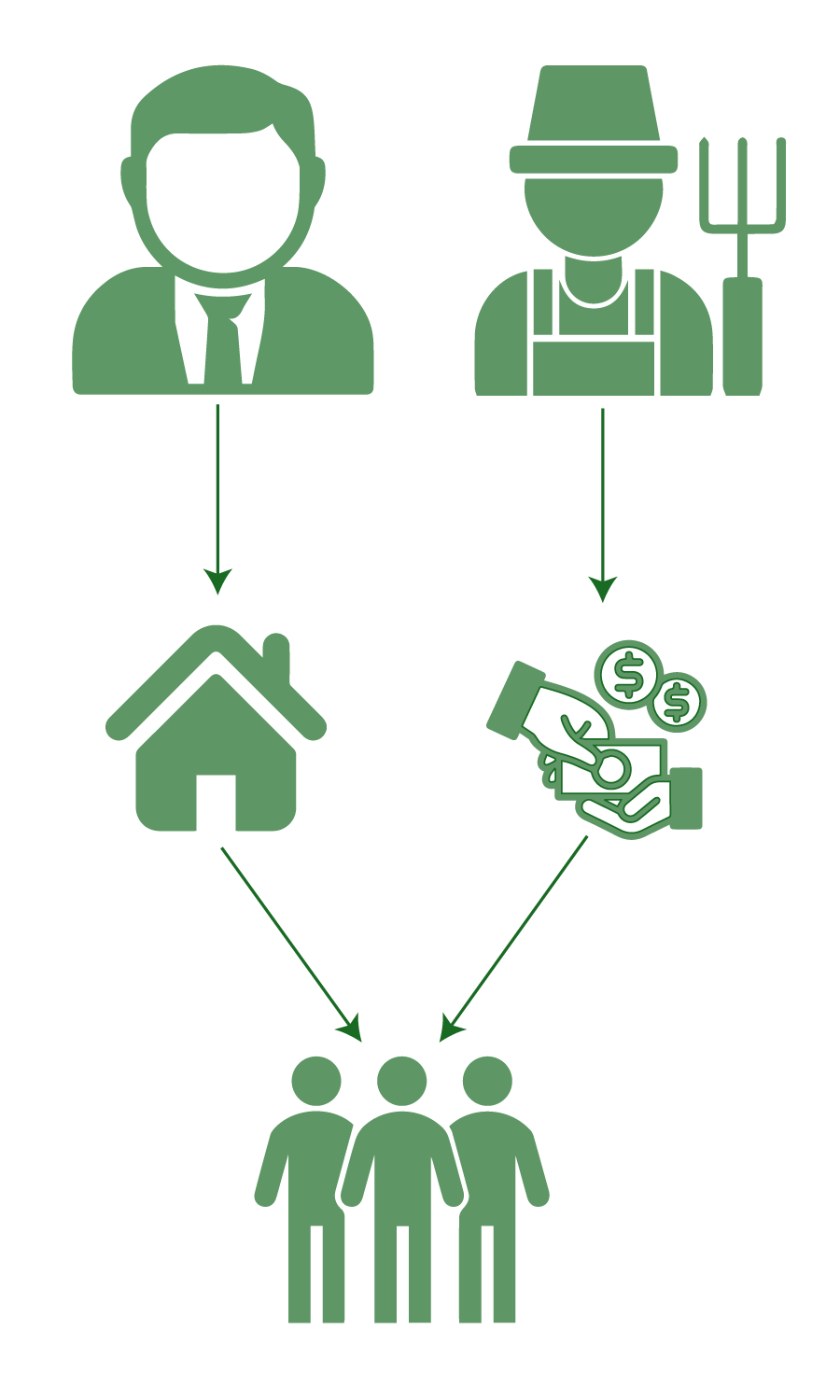

Diagram for employer-owned housing typology composition

Diagram for Employee Rented/ Owned Typology Composition

The Private Market

Consider This:

Ownership Model

Typologies

Barrack style housing camps

Mobile Homes

Apartments

Barracks

Where do Farmworkers Live?

The 2021–2023 Department of Labor survey shows farmworkers most often live in single-family homes (59%), apartments (23%), and mobile homes (17%), with barracks reemerging as an economical option. These familiar labels mask starkly different realities: what appears as a typical home can, for farmworkers, mean crowding, disrepair, or shared facilities. Examining each typology reveals not just where farmworkers live, but how their experiences diverge from mainstream housing norms.

Source: Farmworker Housing: A Photo Essay

Single Family House

Single-family houses are the most common form of farmworker housing, accounting for 59% of the total stock according to the Department of Labor’s 2021–2023 National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS). Within this category, living arrangements vary: on some farms, growers share their homes with hired laborers, while elsewhere farmworkers reside with their families and commute daily.

Yet, while these tends to be the nicer housing stocks for farmworkers, study by the Housing Assistance Council (HAC) found that nearly one-third of these units are moderately or severely substandard. Overcrowding, inadequate plumbing or heating, and chronic disrepair are widespread. In the broader American imagination, the single-family home symbolizes stability and autonomy; for many farmworkers, it instead signifies precarity, shared occupancy, and diminished living standards.

Mobile Homes

Mobile homes, built in factories and set permanently on wheeled chassis, provide a comparatively affordable alternative to single-family houses by reducing the costs associated with on-site construction. The National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) reports that roughly 17% of farmworkers live in mobile homes, making them the third most common form of farmworker housing.

However, this affordability is often offset by poor living conditions. A Housing Assistance Council (HAC) study found mobile homes to be the most frequently neglected housing type, with 44% of those occupied by farmworkers classified as moderately or severely substandard. Among all the issues, peeling paint, broken windows, trash in the yard, and sagging gutters appear to be the most prominent.

Apartments

Apartments—ranging from duplexes to quadplexes—offer a denser form of housing than single-family homes or mobile homes. This typology is the second most common among farmworkers in the United States, accounting for 23% of all farmworker housing in 2021–2022.

These units appear in a variety of forms and scales. In many cases, large apartment buildings are used to accommodate as many workers as possible, with beds filling every available room. Older complexes, such as the Pioneer Hi-Bred International Labor Camp apartments, are often overcrowded and marked by significant interior deterioration. By contrast, newer developments, like the Walnut & Third housing complex completed by Avila Construction in Greenfield, CA, in 2024, are organized more like conventional apartment layouts, though each bedroom typically holds two to four beds. Though the supply of these projects is significantly disproportionate to their demand.

Barrack-Style Housing

Barrack-style houses are long rectangular buildings divided linearly into individual rooms furnished with bunk beds. Depending on the size of the farm, these structures may exist as a single independent building or as part of a larger camp consisting of dozens of barracks arranged with shared facilities such as a community center and health clinic. Rooms are typically equipped with basic cooking appliances, while bathrooms and laundry facilities are located in separate buildings. In the mid-1900s, worker barrack camps such as the Caldwell Labor Camp and the El Milagro Camp housed hundreds of farmworkers.

Crowding and poor maintenance remain the most pressing issues in this housing type. The Housing Assistance Council (HAC) reported that 36.6% of barrack-style houses are moderately or severely substandard. Weak inspection routines contribute to persistent overcrowding, rooms designed for four beds may end up accommodating ten or more people wherever space can be found.

Inspection record from the Illinois Department of Public Health dated 2018, indicating a violation in a farmworker housing, including: a Missing sink handle, running toilet, and rodent activity.

Inspection form

Housing and Health Implication

Farmworkers live stressful and demanding lives, and inadequate housing often compounds that burden. Crowded or poorly maintained living environments heighten daily stress, while exposure to unsafe or unhealthy conditions adds another layer of strain. In contrast, stable and well-kept housing can serve as a buffer, easing pressure rather than intensifying it.

Studies from the Wake Forest School of Medicine emphasize that poor housing not only elevates stress but also weakens social ties and restricts healthy routines, whereas adequate housing fosters resilience. These effects build over time and across generations: overcrowding, heat, and instability manifest as chronic illness, anxiety, or depression, and shape children’s development in lasting ways. The surrounding neighborhood further reinforces these disparities, as isolation, segregation, and limited access to services magnify the health inequities tied to place.

Health of Farmworkers

Exposure to substandard living conditions can have long-term impact on the mental and physical health of farmworkers and their families, many consisting of children

The red circle is the code-required square footage a person needs

So, who is responsible?

Between 2021-2022, 56% of all crop workers rented their housing from someone who's neither a family or the employer. With the houses becoming more and more expensive, rental options for farm workers are more often to be more severely substandard than employer provided housing options.

Privately Rented Housing

Privately Rented Housing

Privately rented farmworker housing generally refers to housing that farmworkers obtain on the open rental market rather than through their employer. Privately rented units are leased from private landlords, property managers, or individual owners, just like any other tenant arrangement.

Employer Provided Housing

Privately Rented Housing

Employer-provided housing refers to housing that is supplied, managed, or arranged directly by the agricultural employer for their workers. It is most often tied to employment status and is either free or provided at a reduced cost as part of the job arrangement.

Between 2021-2022, 56% of all crop workers rented their housing from someone who's neither a family or the employer. With the houses becoming more and more expensive, rental options for farm workers are more often to be more severely substandard than employer provided housing options as they are not subjected to inspections

% of Total Farmworker Housing Stock

Ownership Model and Unit Condition

So, who is responsible?

Between 2021-2022, 56% of all crop workers rented their housing from someone who's neither a family or the employer. With the houses becoming more and more expensive, rental options for farm workers are more often to be more severely substandard than employer provided housing options.

Between 2021-2022, 56% of all crop workers rented their housing from someone who's neither a family or the employer. With the houses becoming more and more expensive, rental options for farm workers are more often to be more severely substandard than employer provided housing options as they are not subjected to inspections

% of Total Farmworker Housing Stock

Ownership Model and Unit Condition

Employer-provided housing refers to housing that is supplied, managed, or arranged directly by the agricultural employer for their workers. It is most often tied to employment status and is either free or provided at a reduced cost as part of the job arrangement.

Privately rented farmworker housing generally refers to housing that farmworkers obtain on the open rental market rather than through their employer. Privately rented units are leased from private landlords, property managers, or individual owners, just like any other tenant arrangement.

Privately Rented Housing

Employer Provided Housing

Why does employer-provided housing have the potential of being safer for farmworkers?

Employer Provided Housing

In contrast to the private rental markets, employer provided housings has more systems of regulation to help ensure farmworker housings are meeting humane standards.

These codes includes

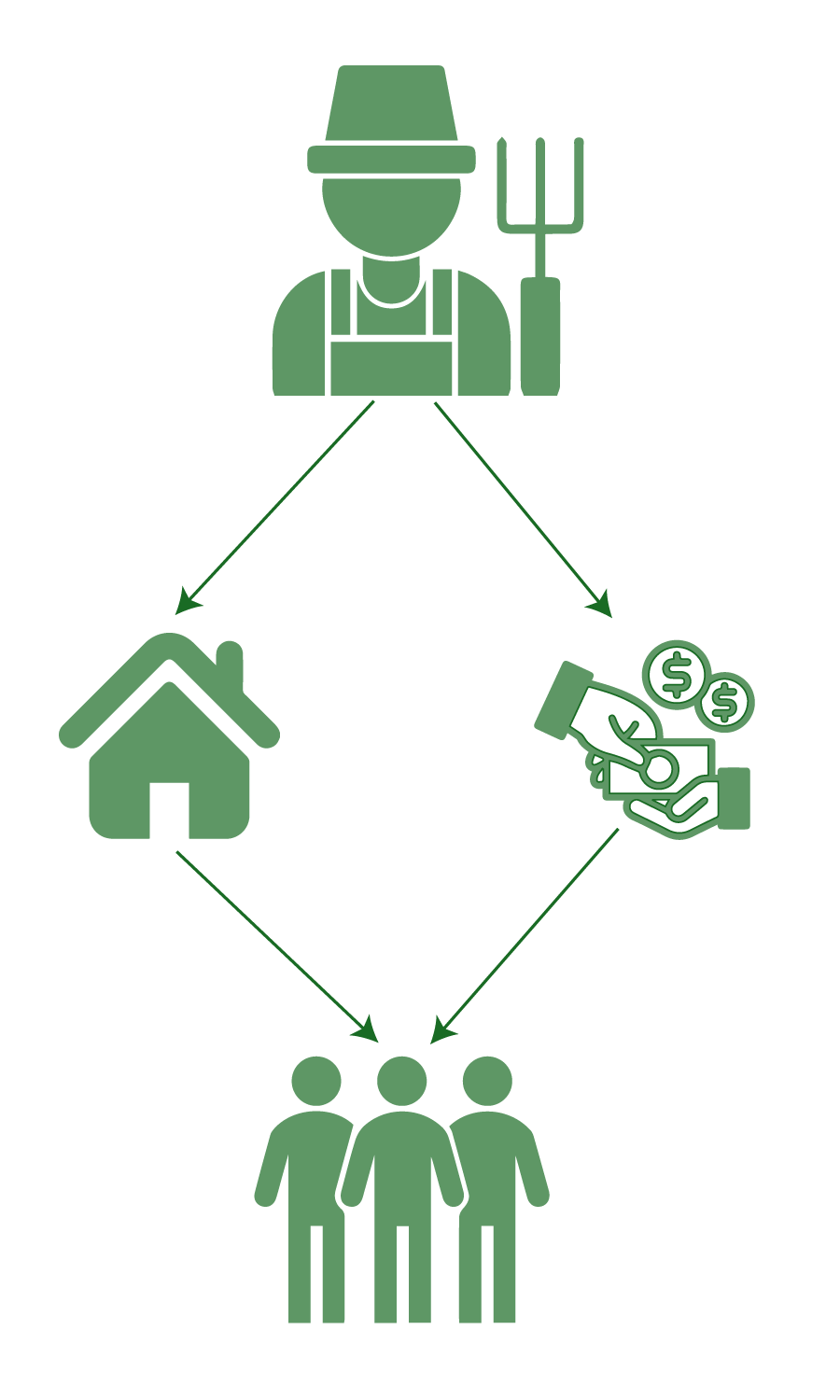

Who Sustains Farmworkers?

Why Employer Units Are Less Likely to Be Substandard

Standards for Employer-Provided Housing

Employers who provide housing must pass state and federal code inspections before workers can move in. These inspections ensure that each dwelling has running water, adequate plumbing, electricity, safe food storage, and enough square footage per worker. These guardrails are designed to protect workers from the substandard and overcrowded conditions often seen in the private rental market.

At the federal level, two frameworks set the floor:

-

Migrant & Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act requires that migrant worker housing meet health-and-safety standards and be inspected/authorized before workers move in.

-

OSHA 29 CFR §1910.142 (Temporary Labor Camps) sets the national baseline, covering water, sewage, bathing/laundry, etc.

-

H-2A rules require employers to provide no-cost housing that meets agricultural-housing standards.

Incentives for farm owners

Offering quality housing helps farms attract experienced crews, reduce turnover, and stabilize productivity. Many growers now build beyond minimum codes (privacy, modern kitchens, safer layouts) because it directly improves retention and performance.

In Salinas Valley, CA, Tanimura & Antle’s Spreckels Crossing apartments became a competitive advantage: by providing clean, modern units near the fields, the company drew reliable crews, eased labor shortages, and cut crop losses, illustrating how better housing can be a bottom-line strategy, not just a compliance box.

The Cost Challenge

Yet, these high-quality projects are expensive to build and maintain. Construction costs can exceed $400k per unit, putting them out of reach for many small- and mid-sized farms. This is where funding becomes critical: grants, low-interest loans, and public-private partnerships make it possible for growers to provide safe, dignified housing without shouldering the full financial burden alone.

Federal Grants and Loans

While there are federal and local programs designed to help farmers secure financing, a closer look at funding availability reveals that demand far outweighs supply. In 2024, the combined budget for USDA Section 514/516 programs totaled only about $22.5 million.

Access to loans remains one of the most pressing challenges in farmworker housing development today.

Program Name | Coverage / Max Funding | Financing Structure | Geography Served |

|---|---|---|---|

USDA Farm Labor Housing (FLH) � Off?Farm Direct Loans & Grants (Sections 514/516) | Loans: up to 100% of allowable total development cost; Grants: up to 90% of development cost (balance via 514 loan or other). | Direct 1% fixed-interest loans (?33 years) and capital grants for off?farm projects; can combine with LIHTC/HTF/HOME. | Federal (nationwide, primarily rural; some nearby urban exceptions allowed). |

USDA Farm Labor Housing � On?Farm Loans (Section 514) | Loans: up to 100% of allowable total development cost; no grants for on?farm. | Direct 1% fixed-interest loans, up to 33?year term; first?come until funds depleted. | Federal (nationwide, rural). |

HUD National Housing Trust Fund (HTF) | Annual formula allocations to states (e.g., ~$223M total in 2025 across all states). Used as gap financing for extremely low?income units. | Federal block grant to states; states award project grants/loans for new construction, rehab, acquisition; ?30?year affordability for rentals. | Federal via states (nationwide). |

HUD HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) | Approx. $1.5B/year nationally; states/localities set per?project limits; supports acquisition, new construction, rehab. | Federal block grant to states/localities; can be passed as grants or low?interest/deferred loans; match typically required. | Federal via states/localities (nationwide). |

New York State Farmworker Housing Program (HCR) � No?Interest Loans via Farm Credit East | Up to $200,000 per borrower per year; revolving fund currently $15M. | 0% interest loan (10?year amortization) with a one?time 5% origination/servicing fee amortized over the term; for new construction or rehab; code compliance priority. | New York State. |

California � Joe Serna, Jr. Farmworker Housing Grant (FWHG) | Varies by NOFA; funds multifamily new construction/rehab and single?family assistance. | Deferred?payment loans for multifamily; grants for single?family new construction or owner?occupied rehab. | California. |

California � Office of Migrant Services (OMS) | State?owned/operated seasonal rental housing; program funding varies by budget (capital & operations historically). | State program providing and operating seasonal rental housing for migrant farmworkers/families; not a developer grant but a direct state service. | California. |

Washington State � Housing Trust Fund (HTF) / Farmworker Housing | Competitive capital awards; amounts vary by round; can pair with federal HTF/HOME/LIHTC. | State loans and grants for permanent farmworker housing; capital & operating support for seasonal; emergency assistance. | Washington State. |

Oregon � Agriculture Workforce Housing Tax Credit (AWHTC) | State income tax credit equal to 50% of eligible project costs; biennial cap (e.g., $16.75M). | Transferable state tax credit to investors/owners financing on? or off?farm agricultural workforce housing; 10?year use requirement. | Oregon. |

Oregon � Agriculture Workforce Housing Grant (ODA) | $5M (2023�2026) statewide for health/safety improvements to existing ag workforce housing; per?project awards vary. | State grants to improve health and safety of existing agricultural workforce housing. | Oregon. |

US Dept. of Labor � Grants for Safe & Sanitary Farmworker Housing Services | e.g., $6.5M announced in 2024 across targeted states; amounts vary by grantee. | Competitive grants to organizations to improve access to safe/sanitary housing (services & coordination; typically not bricks?and?mortar construction). | Federal (targeted states per NOFO). |

Program Name | Coverage / Max Funding | Financing Structure | Geography Served | More Info (URL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

USDA Farm Labor Housing On Farm Loans (Section 516) | Grant covers up to 90% of development cost to purchase, build or improve housings for farmworkers | 90% covered by 516 Grant | Federal | |

USDA Farm Labor Housing On Farm Loans (Section 514) | Loans: up to 100% of allowable total development cost | Direct 1% fixed-interest loans, up to 33 year term; first come until funds depleted. | Federal | https://www.rd.usda.gov/programs-services/multifamily-housing-programs/farm-labor-housing-loans |

New York State Farmworker Housing Program (HCR | Up to $200,000 per borrower per year; revolving fund currently $15M. | 0% interest loan (10 year amortization) with a one-time 5% origination/servicing fee amortized over the term; for new construction or rehab; code compliance priority. | New York State | https://hcr.ny.gov/farmworker-housing-program-fwh |

California Joe Serna, Jr. Farmworker Housing Grant (FWHG) | Varies by NOFA; funds multifamily new construction/rehab and single family assistance. | Deferred payment loans for multifamily; grants for single family new construction or owner occupied rehab. | California | https://www.hcd.ca.gov/grants-and-funding/programs-active/joe-serna-jr-farmworker-housing-grant |

Washington State Housing Trust Fund (HTF) / Farmworker Housing | Competitive capital awards; amounts vary by round; can pair with federal HTF/HOME/LIHTC. | State loans and grants for permanent farmworker housing; capital & operating support for seasonal; emergency assistance. | Washington State | https://www.commerce.wa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/HTF-Reports-Farm-Worker-Housing-Report.pdf |

Oregon Agriculture Workforce Housing Tax Credit (AWHTC) | State income tax credit equal to 50% of eligible project costs; biennial cap $16.75M | tax credit to any costs incurred during construction of agricultural housing. Tax credit may be taken on 50% of the eligible cost paid for farmworker construction | Oregon | https://www.oregon.gov/oda/about-us/Documents/Board%20of%20Agriculture/05-22/factsheet-awhtc.pdf |

Oregon Agriculture Workforce Housing Grant (ODA) | $5M (2023-2026) statewide for health/safety improvements to existing ag workforce housing; per?project awards vary. | %5 million grant to Oregon Department of Agriculture | Oregon | https://www.oregon.gov/oda/agriculture/Pages/workforce-housing-grant.aspx |

Employer-Provided Housing Case Studies

Picture and Links

Picture and Links

Picture and Links

Funded, Built, and Improved

These case studies show what happens when farmers have access to the funds to build clean, code-compliant homes with modern kitchens, safe storage, and reliable utilities. Still, they surface a key tension between quantity and quality: to house more workers within tight budgets, projects often compress room sizes, increase sharing of baths and kitchens, and trim personal storage or communal space.

Location: Ventura, California.

Total cost: ~$13,988,000.

Units: 24 total (23 affordable + 1 manager).

Common Spaces: Computer learning center, community kitchen, community room, courtyard seating.

Other Features: Solar PV, ~600 gal/day, all-electric, drought-tolerant landscaping.

Sources of Funding: LIHTC equity; USDA Section 514 loan; HACSB development & carryback loans; Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco; Ventura County Farmworker Housing funds; deferred developer fee.

Location: Granger, Yakima County, Washington.

Total cost: $3,550,000.

Units: 10 two-bedroom duplex units (hostel-style + family rooms).

Total residents: ~75 capacity at a time.

Common Spaces: Playground.

Other Features: Seasonal dual-use model (winter shelter for families).

Sources of Funding: USDA Section 514/516 Farm Labor Housing Loan & Grant; Washington State Housing Trust Fund; HUD CDBG Housing Enhancement program.

Location: Woodland, Yolo County, California.

Total cost: $36,866,754.

Units: 101 total (100 affordable + 1 manager).

Total Residents: Approximately 300.

Common Spaces: Playground, Community Kitchen and Garden, Counseling Room, Computer Lab, Classroom.

Other Features: Solar PV, Drought-tolerant Landscaping

Sources of Funding: USDA Section 514 loan; Citibank Section 521 rental subsidy increment loan; CA HCD Joe Serna Jr. Farmworker Housing Grant; City of Woodland loan; LIHTC equity; Business Energy Investment Tax Credit.

How can we help make farmworker housings more accessible?

If quality housing benefits both farmowners and farmworkers, but cost remains the biggest obstacle, how can we begin to find ways to make it more accessible?

# of demand for farmworker housing (can simply be the amount of farmworkers documented on census)

# of Employer Provided Housing Supply

The cost of quality

~Costs=

$22k

Per Employee

Housing Vacancy Rate=

~30%-50%/ year

Maintanence Fee

=

~xxxxx / year

While many farmworkers face unsafe, crowded housing in the private market, some employers do provide housing that must meet code requirements. These dwellings are often safer — but they come with high costs that few farms can shoulder without support.